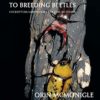

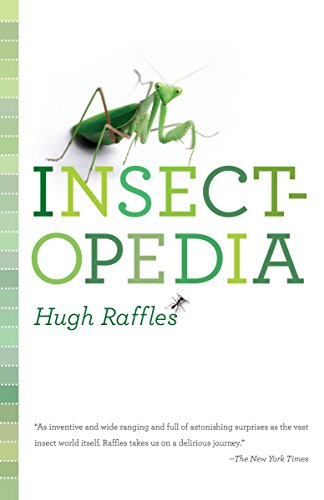

Insectopedia

32,99€ Le prix initial était : 32,99€.32,49€Le prix actuel est : 32,49€. TTC

Auteur: Raffles, Hugh

Marque: Brand: Vintage

Édition: Reprint

Caractéristiques:

- Used Book in Good Condition

Nombre de pages: 480

Éditeur: Vintage

Date de sortie: 22-03-2011

Détails: Présentation de l’éditeur A New York Times Notable BookA stunningly original exploration of the ties that bind us to the beautiful, ancient, astoundingly accomplished, largely unknown, and unfathomably different species with whom we share the world. For as long as humans have existed, insects have been our constant companions. Yet we hardly know them, not even the ones we’re closest to: those that eat our food, share our beds, and live in our homes. Organizing his book alphabetically, Hugh Raffles weaves together brief vignettes, meditations, and extended essays, taking the reader on a mesmerizing exploration of history and science, anthropology and travel, economics, philosophy, and popular culture. Insectopedia shows us how insects have triggered our obsessions, stirred our passions, and beguiled our imaginations. Extrait Air 1. On August 10, 1926, a Stinson Detroiter SM-1 six-seater monoplane took off from the rudimentary airstrip at Tallulah, Louisiana. The Detroiter was the first airplane built with an electric starter motor, wheel brakes, and a heated cabin, but it was not a good climber, so the pilot leveled off quickly, circled the airstrip and surrounding landscape, held open the specially fitted sticky trap beneath the plane’s wing for the designated ten minutes, and soon returned to land. As he touched down, P. A. Glick and his colleagues at the Division of Cotton Insect Investigations of the U.S. Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine ran out to meet him. It was a historic flight: the first attempt to collect insects by airplane. Glick and his associates, as well as researchers at the Department of Agriculture and at regional organizations such as the New York State Museum, were trying to discover the migration secrets of gypsy moths, cotton bollworm moths, and other insects that were munching their way through the nation’s natural resources. They wanted to predict infestations, to know what might happen next. How could they contain these insect enemies if they didn’t know where, when, and how they traveled? 2. Before Tallulah, high-altitude entomology had barely got off the ground. Researchers sent up balloons and kites fitted with hanging nets, climbed up pylons, and pestered lighthouse keepers and mountaineers. But armed now with the new airplane technology, Glick went down to Tlahualilo in Durango, Mexico. There, 3,000 feet above the valley plain, his pilots trapped the pink bollworm moth, a feared invader of the U.S. cotton crop. Face-to-face with the unanticipated scale of his task, Glick wrote tersely that « the pink bollworm moths are carried in the upper air currents for considerable distances. » There were only a few flies and wasps in that first trap at Tallulah. But over the next five years, the researchers flew more than 1,300 sorties from the Louisiana airstrip and captured tens of thousands more insects at altitudes ranging from 20 to 15,000 feet. They generated a long series of charts and tables, cataloguing individual insects of 700 named species according to the height at which they were collected, time of day, wind speed and direction, temperature, barometric pressure, humidity, dew point, and many other physical variables. They already knew something about long-distance dispersal. They had heard about the butterflies, gnats, water striders, leaf bugs, booklice, and katydids sighted hundreds of miles out on the open ocean; about the aphids that Captain William Parry had encountered on ice floes during his polar expedition of 1828; and about those other aphids that, in 1925, made the 800-mile journey across the frigid, windswept Barents Sea between the Kola Peninsula, in Russia, and Spitsbergen, off Norway, in just twenty-four hours. Still, they were taken aback by the enormous quantities of animals they were discovering in the air above Louisiana and unashamedly astonished by the heights at which they found them. All of a sudden, it seemed, the heavens had opened. Unmoored, they turned to the oc

Soyez le premier à laisser votre avis sur “Insectopedia” Annuler la réponse

Vous devez être connecté pour publier un avis.

Avis

Il n’y a pas encore d’avis.